Philosophy Pages

| Dictionary | Study Guide | Logic | F A Q s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Timeline | Philosophers | Locke | |||

Philosophy Pages

| Dictionary | Study Guide | Logic | F A Q s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Timeline | Philosophers | Locke | |||

|

Life and Works . . Inequality . . Social Contract . . General Will Bibliography Internet Sources |

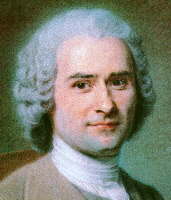

As a brilliant, undisciplined, and unconventional thinker, Jean-Jacques Rousseau spent most of his life being driven by controversy back and forth between Paris and his native Geneva. Orphaned at an early age, he left home at sixteen, working as a tutor and musician before undertaking a literary career while in his forties. Rousseau sired but refused to support several illegitimate children and frequently initiated bitter quarrels with even the most supportive of his colleagues. His autobiographical Les Confessions (Confessions) (1783) offer a thorough (if somewhat self-serving) account of his turbulent life.

Rousseau first attracted wide-spread attention with his prize-winning essay

Discours sur les Sciences et les Arts (Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts) (1750),

in which he decried the harmful effects of modern civilization. Pursuit of the arts and sciences, Rousseau argued, merely promotes idleness, and the resulting political inequality encourages alienation.

He continued to explore these themes throughout his career, proposing in Émile, ou l'education (1762)

a method of education that would minimize the damage by noticing, encouraging, and following the natural proclivities of the student instead of striving to eliminate them.

in which he decried the harmful effects of modern civilization. Pursuit of the arts and sciences, Rousseau argued, merely promotes idleness, and the resulting political inequality encourages alienation.

He continued to explore these themes throughout his career, proposing in Émile, ou l'education (1762)

a method of education that would minimize the damage by noticing, encouraging, and following the natural proclivities of the student instead of striving to eliminate them.

Rousseau began to apply these principles to political issues specifically in his

Discours sur l'origine et les fondements de l'inégalité parmi les hommes (Discourse on the Origin of Inequality) (1755),

which maintains that every variety of

injustice found in human society is an artificial result of the control exercised by defective political and intellectual influences over the healthy natural impulses of otherwise noble savages.

The alternative he proposed in

Du contrat social

(On the Social Contract) (1762)

is

a civil society voluntarily formed by its citizens and

wholly governed by reference to the

general will

[Fr. volonté générale] expressed in their unanimous consent to authority.

The alternative he proposed in

Du contrat social

(On the Social Contract) (1762)

is

a civil society voluntarily formed by its citizens and

wholly governed by reference to the

general will

[Fr. volonté générale] expressed in their unanimous consent to authority.

Rousseau also wrote Discourse on Political Economy (1755), Constitutional Program for Corsica (1765), and Considerations on the Government of Poland (1772). Although the authorities made every effort to suppress Rousseau's writings, the ideas they expressed, along with those of Locke, were of great influence during the French Revolution. The religious views expressed in the "Faith of a Savoyard Vicar" section of Émile made a more modest impact.

|

Recommended Reading:

Primary sources:

Secondary sources:

Additional on-line information about Rousseau includes:

|