Philosophy Pages

| Dictionary | Study Guide | Logic | F A Q s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Timeline | Philosophers | Locke | |||

Philosophy Pages

| Dictionary | Study Guide | Logic | F A Q s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | Timeline | Philosophers | Locke | |||

|

Life and Works . . Freedom . . Responsibility . . Self-Deception . . Despair Bibliography Internet Sources |

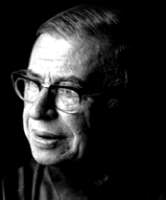

Educated in his native Paris and at German universities, Jean-Paul Sartre taught philosophy during the 1930s at La Havre and Paris. Captured by the Nazis while serving as an Army meteorologist, Sartre was a prisoner of war for one year before returning to his teaching position, where he participated actively in the French resistance to German occupation until the liberation.

Recognizing a connection between the principles of

existentialism and the more practical concerns of social and political struggle, Sartre wrote not only philosophical treatises but also novels, stories, plays, and political pamphlets. Sartre's personal and professional life was greatly enriched by his long-term collaboration with Simone de Beauvoir.

Although he declined

the Nobel Prize for literature in 1964, Sartre was one of the most respected leaders of post-war French culture, and his funeral in Paris drew an enormous crowd.

Although he declined

the Nobel Prize for literature in 1964, Sartre was one of the most respected leaders of post-war French culture, and his funeral in Paris drew an enormous crowd.

Sartre's philosophical influences clearly include

Descartes,

Kant,

Marx,

Husserl, and

Heidegger.

Employing the methods of descriptive phenomenology to new effect, his

l'Être et le néant (Being and Nothingness) (1943) offers an account of

existence in general, including both the being-in-itself of objects that simply are and the being-for-itself by which humans engage in independent action.

Sartre devotes particular concern to emotion as a spontaneous activity of

consciousness projected onto reality.

Empasizing the radical

freedom of all human action, Sartre warns of the dangers of

mauvaise foi

(bad faith), acting on the

self-deceptive motives by which people often try to

elude responsibility for what they do.

In the lecture l'Existentialisme est un humanisme ("Existentialism is a Humanism") (1946), Sartre described the human condition in summary form: freedom entails total responsibility, in the face of which we experience anguish, forlornness, and despair; genuine human dignity can be achieved only in our active acceptance of these emotions.

Sartre's complex and ambivalent intellectual relationship with traditional Marxism is more evident in Critique de la raison dialectique (Dialectical Reason) (1960), an extended sociological and philosophical essay.

|

Recommended Reading:

Primary sources:

Secondary sources:

Additional on-line information about Sartre includes:

|